Hogarth’s popularity with both artists and the public has endured for over two hundred years, and his work has provided inspiration to successive generations. Hockney, Shonibare and Perry not only update Hogarth’s searing social commentary, they also add their own personal concerns to the creative dialogue. Commissioning an emerging female artist to respond to Hogarth’s work, the Foundling Museum further developed the conversation.

Hogarth, an active Governor of the Foundling Hospital, burst onto London’s artistic scene in the first half of the eighteenth century, creating a new form of narrative painting with his modern moral tales. Published as a set of engravings in 1735 in order to reach a wide audience, A Rake’s Progress follows the rise and fall of young heir and spendthrift, Tom Rakewell. On inheriting his miserly father’s fortune, Tom embraces a world of foppery and pretention, descending into a spiral of debauchery and debt, which leads him to prison and eventually, the madhouse. The series is an unflinching portrayal of the corruption, hypocrisy, vice and occasional virtue of eighteenth-century London, presented with Hogarth’s typical wit and eye for detail.

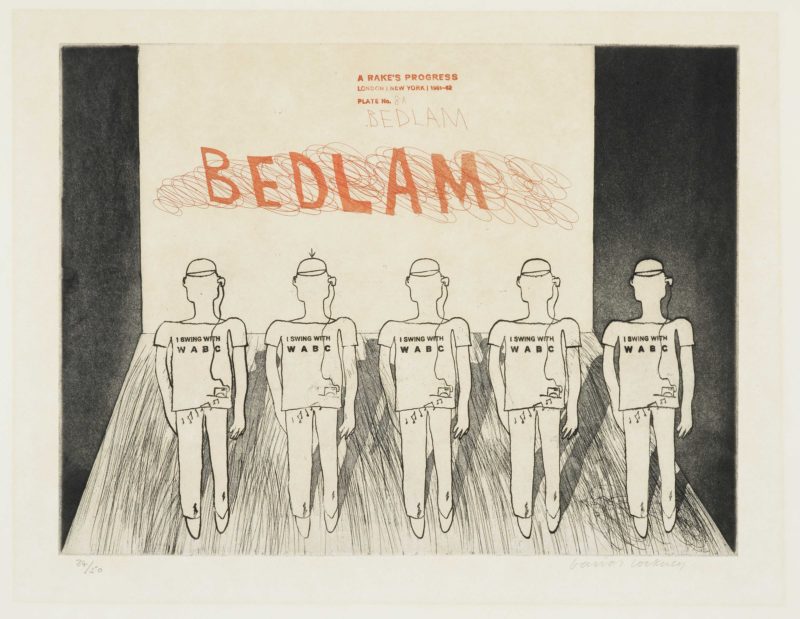

Hockney’s semi-autobiographical A Rake’s Progress (1961-3), charts the adventures of a young, provincial gay artist in New York. His sixteen etchings were produced as a direct response to his first trip to America and were initially intended to mirror the titles of Hogarth’s eight etchings. However, on return to London, Hockney soon added a further eight plates. His series explores themes of youth and the city, freedom and moral corruption. Like Hogarth, Hockney’s story ends in ‘Bedlam’.

Shonibare’s Diary of a Victorian Dandy (1998) plays with notions of culture, identity and history, by transplanting the tale to the heyday of the British Empire and making the protagonist black. Originally commissioned by Iniva for the London Underground, Shonibare’s series follows the Rake over a 24 hour period. Like Hogarth, Shonibare’s depiction of youthful hedonism, lust and wealth is alive with detail, while also highlighting the relationship between the luxury goods trade and slavery.

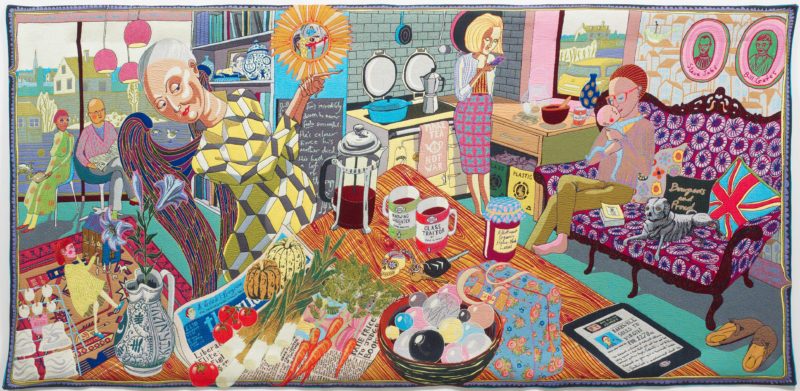

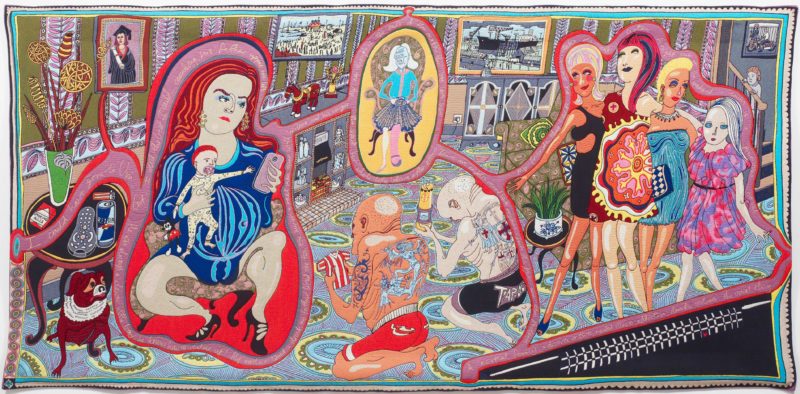

Perry’s hugely popular tapestry series The Vanity of Small Differences (2012) explores the complexities of the British class system, as played out through ideas of taste. Like Hogarth, Perry’s protagonist Tim Rakewell journeys through the classes, his progress highlighting the obsessions, traits and hypocrisies of each. Perry surrounds Rakewell with the ‘taste signifying’ objects he discovered on his journey through Britain for the television documentary, ‘All in the Best Possible Taste with Grayson Perry’.

Hogarth was a supporter of the Foundling Hospital from the outset. He designed the Hospital’s coat of arms, and it is thought he designed the children’s uniforms and the decorative scheme in the Court Room. Most importantly, he donated the first artwork to the Hospital: his magnificent portrait of Thomas Coram, and encouraged all the leading artists of the day to do the same, thereby creating England’s first public art gallery. His involvement in the Hospital was a catalyst for encouraging artists of all disciplines to become ‘socially engaged’. It also enabled him to promote the work of emerging artists such as Thomas Gainsborough, and to establish a community of British artists that led to the founding of the Royal Academy.

This doesn’t feel like a static exhibition. It is mobile, dynamic. The very act of moving through the building reflects the narrative movement of the different Progresses, and imparts a feeling of translation, of conversation.

What’s remarkable (and alarming) is quite how alike Hogarth’s world is to our own.